Aid Amidst the Flames of War | The Hump: An Air Route Forged by Lives

Editor’s Note

During the arduous all-out War of Resistance, the unwavering spirit and sacrifice of the Chinese military and people in their fight against the invaders earned the support and sympathy of the international community. Friends from across five continents and overseas Chinese offered their solidarity and support in various ways. Many viewed aiding China as part of their duty in the global fight against fascism.

This year marks the 80th anniversary of the victory of the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression and the World Anti-Fascist War. The Memorial Hall Media Center has launched a special series titled “Aid Amidst the Flames of War,” highlighting the stories of international friends and overseas Chinese who fought alongside the Chinese people against Japanese fascism. Today, we present the first story: “The Hump: An Air Route Forged by Lives.”

The U.S. Time once described the tragedy of the Hump Route as follows:“On clear days, we could navigate by the reflections from the wreckage of our comrades’ crashed planes. We named this valley, strewn with aircraft debris, ‘Aluminum Valley.’”

In 1942, when Japan occupied Burma and cut off China’s last international link to the outside world, China and the United States were forced to open a new supply route—the Hump. This air route, which operated from 1942 until the end of World War II, played a critical role in delivering war supplies for the fight against Japan.

Flying the Hump

How Dangerous Was the “Death Route”?

The Hump was the most perilous and deadly air route of World War II. Chinese and American pilots braved extreme natural conditions and constant threats of interception by Japanese forces.

View of the Himalayas from a plane

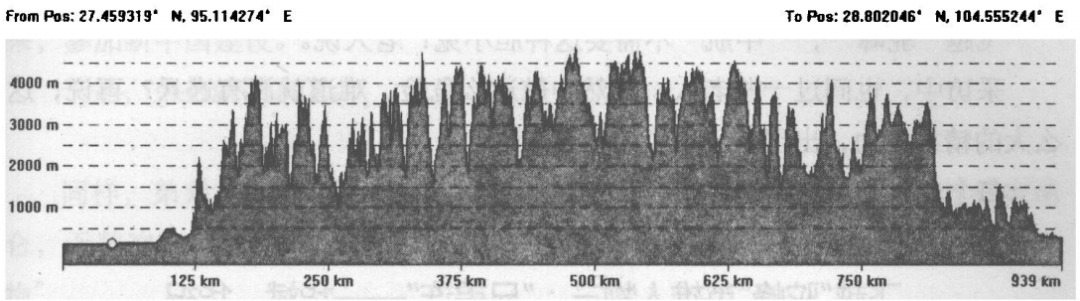

The route began in Assam, India, and headed east across the Himalayas, Gaoligong Mountains, and Hengduan Mountains into Yunnan and Sichuan in China. Elevations ranged from 4,500 to 5,500 meters, with peaks reaching 7,000 meters. The route passed through tropical, alpine, and subtropical climates, with rapidly changing weather and frequent turbulence, posing severe risks to pilots.

The elevation chart reveals the extreme difficulty of the Hump Route

The U.S. journalist Bai Xiude wrote: “The Hump drove many men mad, killed others, and sent more home with tropical diseases. Some servicemen called it ‘hell in the air.’”

The U.S. author Theodore White wrote: “For several months, the Hump Command lost more planes and men than the Fourteenth Air Force, which was directly engaged in combat.”

To avoid Japanese fighter planes, Sino-American transport aircraft had to take off from the Tingjiang River area, head north into Tibet, fly close to the Himalayas, then turn east over the Hengduan range.

A pilot shows bullet holes in the wing

This detour increased both the distance and the difficulty of the flights. The danger led to a high crash rate, and both the Chinese and American air forces made heavy sacrifices along this route.

How Important Was the “Aerial Lifeline”?

The Hump was one of the busiest air routes in the final years of WWII. According to statistics, in October 1944, it averaged 297.7 flights per day. By June 1945, the daily average rose to 622 flights, roughly one plane every minute.

A loaded plane ready to fly over the Hump

Bai Xiude wrote: “Lying in the grass beside the runway at Kunming Airfield, looking up at the sky, you could always see a mix of C-54s, B-24s, L-5s, and L-4s, all crowding the skies.”

Over three years, more than 800,000 tons of materials were transported to China, with 81% of wartime aid delivered via the Hump. Supplies included weapons, ammunition, medical materials, vehicles, machinery, and military garments.

Gasoline being loaded into planes for transport to China

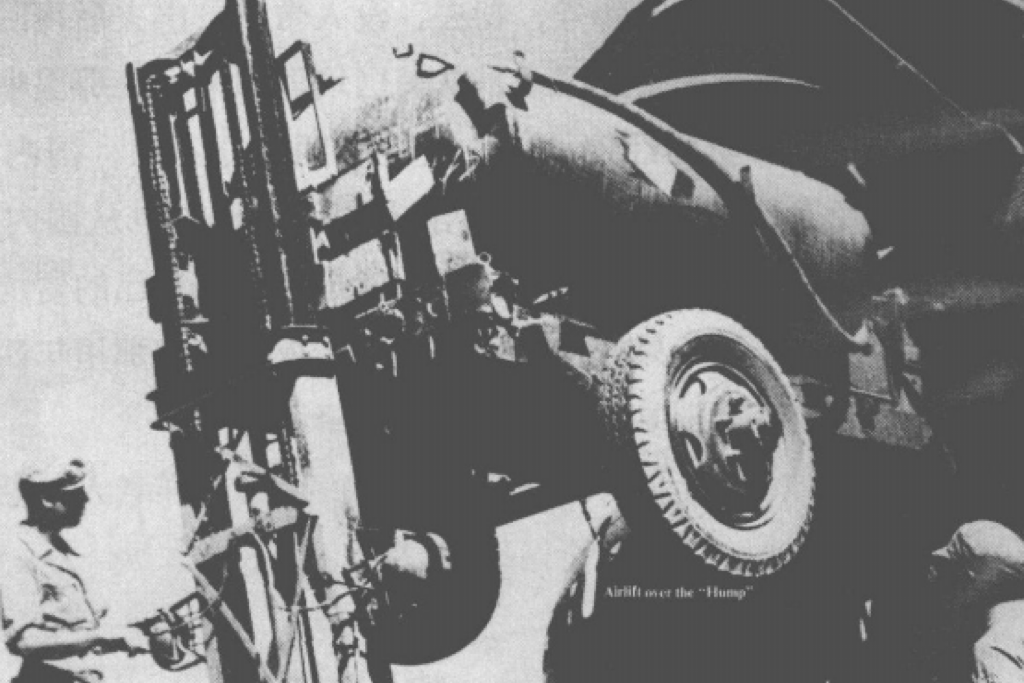

Tanker trucks loaded onto aircraft

China also transported over 150,000 tons of goods abroad via the Hump, including strategic materials like tungsten, tin and other specialty minerals, crucial for sustaining the wartime economy in China’s southwest. In terms of personnel transportation, tens of thousands of troops and refugees from China who lost the Burma Campaign, troops who traveled from China's Yunnan Province to India for military training, and Allied troops who traveled from India to fight in northern Burma were transported via the Hump.

Airdrop operations over the Myitkyina region

To construct and maintain the airfields, China invested massive manpower and resources. In Sichuan alone, over 1.5 million civilian workers built five military airfields near Chengdu in record time. When runways were bombed or damaged, laborers risked their lives to repair them. To protect the route, Chinese civilians and military formed an aerial intelligence network that provided crucial reports to the U.S. about Japanese air movements.

After crossing the Hump, a plane plunges into the river near the airfield

As China’s only external communication link during wartime, the Hump Route was critical in breaking the Japanese blockade and enhancing international cooperation.

How Many Chinese and American Pilots Died on the Hump?

Flying over icy peaks and deep valleys, amidst strong winds and snowstorms, Chinese and American pilots shared life-and-death moments in their missions over the Himalayas.

According to incomplete statistics, the U.S. military lost 563 aircraft and over 1,500 crew members on the Hump. China National Aviation Corporation, with about 100 transport aircraft, flew 80,000 sorties and lost 48 planes and 168 pilots.

Crew members pose with snow-capped peaks in the background

Most of the fallen pilots were in their early twenties. Due to the extreme terrain, the remains of many heroes have never been recovered.

In January 1945, 21-year-old Jay Vinyard flew a mission delivering supplies to Kunming. Before takeoff, weather analysts marked the Hump area in white, indicating strong winds throughout the region.

Jay Vinyard

Shortly after takeoff, Vinyard lost contact with the ground. Vinyard recalled, “We huddled in the cockpit, flying blind in the pitch-dark night sky. You could’t see anythi

ng outside. The radio crackled constantly with distress calls from other aircraft…” That night, the U.S. Army Air Forces lost nine planes and 42 crew and passengers.

Chinese pilot Xu Dingzhong wrote in his autobiography Unforgettable Hump Flight:"Each pilot logged at least a hundred flying hours per month—some even hundreds. On clear days, we could sometimes see silver glints along the route—wreckage of downed planes, either deep in dense forests or at the base of sheer cliffs…."

Xu Dingzhong

The U.S. pilot Wesley Fronk once said: “I will never forget the faces of my fallen comrades, nor the courage of the Chinese people. The younger generation must always remember why we came to China—because the people cried for justice and needed peace.”

Today, the tragic stories of these heroes live on. For years, China and the U.S. have worked together to locate and repatriate the remains of those who perished on the Hump.

In 2015, a U.S. official stands beside the statue of General Claire Chennault, holding a box containing the remains of an American soldier who died on the Hump